Grains are technically classified as a hard, small, and dry seed, with or without an attached hull. Although the definition sounds rather boring, today’s top chefs and developers have been demonstrating a renewed interest in using whole grains, especially “ancient” or “heritage” grains.

According to the Whole Grains Council, a part of the non-profit Oldways Preservation Trust, wholesome whole grains have been in vogue for a number of years now. While chefs and bakers focus on the culinary benefits of these grains, consumers have become more attuned to them than ever for other attributes, such as nutrition, sustainability, and the status of many of them as non-GMO.

Table of Contents

Restaurant chefs and artisanal bakers have dived right into the trend of using heritage grains, interest also has migrated to prepared food product developers, mainstream foodservice establishments, and even some beverage makers.

While the previous wave of interest in whole grains focused primarily on the more typical offerings of whole wheat, oats, blue corn, and white barley, with scattered introductions to grains such as amaranth or teff. The new wave is digging deeper—and more colorful.

Recent hot trends in the marketplace include black and purple barley, black and purple rice, and red and purple corn, as well as some grains that never got their due: sorghum and heritage forms of millet and wheat, such as fonio and kernza. A closer look at these ingredients is warranted.

In the Black

Barley is one of the oldest cultivated foods on Earth. It was consumed in ancient Egypt by the workmen (while the nobility dined on emmer, an ancient species of wheat). In fact, barley became such an important staple in Egypt that became a symbolic part of religious celebrations. Wild barley still flourishes throughout the Middle East.

The type of barley specifically consumed in ancient Egypt was known as Black Nile barley, and today it is experiencing a resurgence in popularity. Food manufacturers are using the grain whole, flaked, or ground into flour. Similar to black barley are blue barley and purple barley.

Lentz Spelt Farms are specialists in what they have branded “resurgent grains.” In addition to emmer, spelt, farro, einkorn, and other grains, the company has a black barley flour that it uses as a base for pancake mixes.

Fonio—a protein-rich relative of millet from Africa—is a new star on the American culinary scene.

PHOTO COURTESY OF: Yolélé Foods Inc. (www.yolelefoods.com)

Barley flour is versatile enough to be used as a replacement for all-purpose flour in nearly any baking recipe. However, it is important to note that flour replacements vary from 25% to 100%, depending on the application.

For pancakes, 100% of the all-purpose flour can be replaced with barley flour without affecting flavor, texture, or appearance. In biscuits and scones, a 50% replacement will produce a flaky and tender crumb, while providing a nutty flavor.

A 100% replacement of barley flour for all-purpose flour tends to create a crumbly texture and darker color. In yeast-leavened breads, 25% of the all-purpose flour can be replaced without affecting color or elasticity. A 50% replacement in yeast-risen products is not recommended, however, as the dough becomes dense and dry, and full replacement creates a dough that is extremely difficult to work with.

On the other hand, for muffin and tea cake mixes, 50% replacement with barley flour creates a nutty texture, fluffy crumb, and domed cake. (A higher percentage of barley flour would create darker cakes with a dense texture.)

Lentz also provides a type of wild flax known as “camelina” (Camelina sativa), and grünkern, a European version of the increasingly popular green-harvested Middle Eastern wheat, freekeh.

Going Naked

Black Nile barley is a hull-less grain. This is an important trait, caused by a recessive gene. Hulled barley forms a cement-like substance that binds the hull to the kernel, beginning 16 days after pollination. This makes hulled barleys different from other hulled grains like spelt, emmer, and einkorn, in that removal of the barley hull must be done by grinding (instead of dehulling).

“Pearling” barley is such a process. Hull-less barley requires no grinding, truly making it a softer yet still whole-grain product.

The pigment of the black barley is actually a deep purple. It can be used to naturally enhance color in some applications. The color comes from high antioxidant levels contributed by anthocyanins. Anthocyanins are also found in red, blue, and purple plants, such as berries, cabbage, and red beets. However, the compounds are more stable in grains than they are in fruits and vegetables.

Consumers gravitate toward products made with these richly colored grains not only because of the novelty but also for the health benefits. In addition to the anthocyanins and other antioxidants, heritage grains—especially deeply colored ones—are high in fiber, protein, and minerals, particularly selenium.

In addition, all barley varieties are officially FDA-approved to use a “heart healthy” designation, as they are high in fiber, especially beta-glucan fiber. Beta-glucans help manage blood cholesterol levels and have shown prebiotic activity. These compounds also have demonstrated abilities to help regulate blood-glucose, making them ideal for manufacturers seeking to target the growing number of consumers who have diabetes or pre-diabetes.

Colorful grains do impact the final appearance of a formulation. But some chefs use this to an advantage to add depth of color to a product. And when used whole, they can provide visual appeal. Jason Knibb, the award-winning executive chef at Nine-Ten restaurant in La Jolla, California, looks to ancient grains, including black barley, to add variety to his menu. He uses them primarily in vegetarian plates, but notes that they also pair well with meat dishes.

Corn is considered common and even modern, but colorful strains revived from ancient Andean sources show off its historical pedigree.

PHOTO COURTESY OF: Melissa's World Variety Produce Inc. (www.melissas.com)

From Feed to Food

If you ask a roomful of people about sorghum, chances are that few of them will know anything about it. Yet, this less-familiar grain is already, according to the Grains Council of America, “the fifth most important cereal crop in the world, largely because of its drought tolerance and versatility as a food.”

Sorghum has a long history of usage, especially in the Southern half of the US. Until recently, it was used primarily for animal feed, although any good Southerner can attest to the merits of light, molasses-like sorghum syrup on waffles and pancakes.

From an environmental and financial standpoint, sorghum also plays a major role in water conservation, using about one-third less water than comparable crops.

Sorghum’s use in food processing has become more common in the past few years. Kelly Toups, RDN, director of nutrition for Oldways, lists sorghum as “one of the grains that has made the most impressive strides in popularity in the US over the past six years.” She adds that “the prevalence of sorghum [in formulations] has increased fourfold during that time.”

Heirloom versions of familiar grains are often more nutritious as well as more colorful, making them doubly attractive to processors and consumers alike.

PHOTO COURTESY OF: Ardent Mills LLC (www.ardentmills.com)

As grains go, sorghum has numerous bragging rights. Because it does not contain gluten, sorghum is often used in gluten-free foods. The grain is also grown from traditional hybrid seeds, so it is non-GMO. From a health standpoint, some specialty sorghums are high in antioxidants. As health-focused food trends go, sorghum thus fits nicely into several categories.

There are a variety of culinary applications in which sorghum can shine. It has a light color and a neutral, faintly sweet flavor. Ground, it’s an excellent partial replacement for wheat flour in a variety of baked goods, from muffins to pie crust. Sorghum flour has a smooth, non-gritty texture that is well-suited to gluten-free baking.

Sorghum in Action

Sorghum and other ancient grains help to alleviate some of the challenges manufacturers face in producing gluten-free breads. These ingredients allow formulators to create baked goods with the strength and elasticity of a traditional wheat-based product.

The ratio of sorghum flour that can be successfully added to baking recipes is typically 15%-20%. Adding too much sorghum can affect texture, causing baked goods to crumble. One manufacturer of the flour advises adding egg or a starch (such as cornstarch) to help bind the flour, thus preventing crumbling. This should be done at a ratio of 8g starch to 120g flour.

Smart Flour Foods LLC is one processor taking advantage of sorghum’s benefits. The company includes sorghum flour as part of its proprietary blend of ancient grain flours in its gluten-free pizza crusts. “Sorghum flour provides a hearty yet tender texture in baked goods, as well as adding flavor, and a natural sweetness,” says Josh Shurtleff, vice president of operations for Smart Flour.

Aside from baking applications, sorghum can also be used to produce syrups, especially for flavor and texture in marinades, salad dressings, and sauces. Sorghum also lends itself well to popping, similar to popcorn. Several companies already have created snack products from popped sorghum.

Globally, sorghum is used to produce Ethiopian-style flatbreads, beverages (such as the fiery Chinese liquor Maotai), tortillas, couscous, and salads. Sorghum bran also has been used as a natural preservative.

A Sprouting Trend

PHOTO COURTESY OF: Briess Malt & Ingredients Co. (www.briess.com)

Gently soaking whole grains to begin germination (sprouting), then heat treating them to halt the process at the just the right time to preserve the sprouts enhances their nutrition profile and reduces any anti-nutritional compounds. They end up with the peak amount of vitamins, bioavailable minerals, amino acids and nutraceutical phytochemicals. They also develop a sweeter, more complex flavor. From that point, they can be dried or toasted and ground into a whole flour—sprouted grain breads have become particularly popular in recent years—or used to flavor, color, and thicken sauces and gravies.

Fonio and Kernza

The sudden rise of fonio from obscurity to qualifying as the latest “super grain” can be partly attributed to several chefs, including James Beard award winner Pierre Thiam. Thiam first featured fonio in his 2008 cookbook Yolele!, an exclamation that translates to “let the good times roll” in the Wolof language. Fonio has been cultivated in West Africa for thousands of years, and is used in salads, porridges, and stews. It is commonly ground into a flour, too.

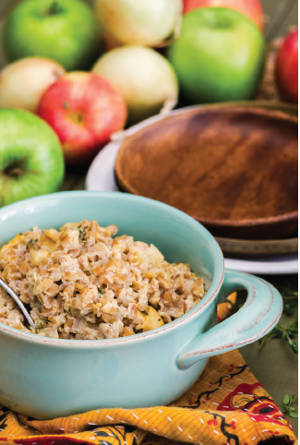

Fonio is a type of millet, described as a cross between quinoa and couscous in both appearance and texture. It has a slightly nutty flavor, which lends itself to a variety of culinary applications. Fonio is also gluten-free. It has been showing up in a variety of recipes, from stuffings and pilafs to salads and fritters.

Thailand has become a leading producer of rice, including the fast-trending Hom Mali rice, red rice, and purple rice—all high in protein and fiber.

PHOTO COURTESY OF: Department of International Trade Promotion, Thai Trade Center (www.thaitradeusa.com)

Most grains are annual crops, planted from seed and grown to maturity, only to produce seed or fruit and then die off within a one-year cycle.

This cycle can create a great deal of environmental strain. It causes disturbances in the soil, which result in a significant amount of soil carbon loss (which ends up in the atmosphere as CO2). It also causes soil erosion, nutrient leakage, and changes in soil organisms.

To overcome these obstacles, farmers may turn to growing perennial plants. Perennial plants do not have to be reseeded or replanted every year, so they do not require annual plowing or herbicide applications. According to The Land Institute, “perennial crops are robust; they protect soil from erosion and improve soil structure. They increase ecosystem nutrient retention, and help ensure food and water security over the long term.”

For these reasons, the arrival of Kernza, a wild relative of wheat that still manages to taste like “traditional” wheat, has been a long time coming. Researchers at The Land Institute have been working to develop the perennial wheat for more than a decade.

Unlike traditional wheats, Kernza has a dense root system up to 10 feet deep. It’s a wheat that manages to have a “typical” wheat flavor, yet it grows more like a grass. For that reason, it can respond to shifts in soil and temperature quickly, taking in water, nitrogen, and phosphorus. Annual wheat doesn’t live long enough to develop thick roots, and requires soil tilling before each planting. But Kernza’s roots hold soil in place, preventing erosion.

A number of chefs and bakers have begun working with this new strain of wheat, including Chad Robertson of Tartine Bakery in San Francisco, and Zachary Golper, baker and owner of Bien Cuit Bakery in Brooklyn. Now, food giant General Mills is partnering with The Land Institute to commercialize this new variety of wheat for broad use.

Rice To the Occasion

In Thailand, people don’t greet one another by saying, “How are you?” Instead, they ask, “Have you eaten rice today?” Rice is a national staple in Thailand, as it is in much of the rest of the world. “Rice is the life and blood of Thailand,” says Arun Sampanthavivat, owner and executive chef of Arun’s Thai, in Chicago.

It is, therefore, no surprise that Thailand is one of the world’s leading sources for high-quality rice. Thanks to its geography and climate, the country is abundant with natural resources for growing more than 100 varieties of rice. The primary rice types exported from Thailand include Hom Mali (Jasmine rice), Sang Yod (brown rice), Hom Nil (black rice), and Riceberry (purple rice). All of these varieties have a dense nutritional profile, and are high in protein and fiber.

Although low compared to the other countries, especially Asia, rice consumption in the US is double what it was in the 1980s.

PHOTO COURTESY OF: InHarvest Inc. (www.inharvest.com)

Riceberry, or purple rice, is a cross-pollination between Jai Hoom Nin (non-glutinous black rice) and hom mali. It’s non-GMO, high in fiber, and loaded with antioxidants, especially anthocyanins. As with all rice, it is gluten-free, but it also has a good complement of omega-3 fatty acids.

Purple rice is used in multiple culinary applications, where it provides both a rich nutty flavor and deep color. It can be ground to make pancakes with a purple hue, steeped into ice cream for added color and flavor, or simply served as a side dish. It is frequently used in desserts as well.

Long grain, aromatic hom mali rice has more starch than other varieties, a faint vanilla-like aroma, and soft texture. It also is a highly nutritious rice, rich in fiber and B vitamins, plus other key nutrients, appealing to consumers from both a culinary and a health perspective.

The unique flavor of the rice comes from the microclimate of the region where it’s grown, and has earned hom mali rice the Protection Geographical Indication from the EU. When ground into a powder and used as a thickening agent in sauces and soups, it yields a softer texture than cornstarch, according to Sampanthavivat. The Ministry of Commerce and Department of International Trade of Thailand noted that the qualities of Thai hom mali rice recently elevated it to a position of high demand in the global marketplace.

Although popular, ancient forms of wheat and wheat cousins, such as farro, emmer, spelt, einkorn, triticale, and Kamut, are not gluten-free grains.

PHOTO COURTESY OF: Bob's Red Mill Natural Foods Inc. (www.bobsredmill.com)

In fact, consumer use of rice in the US is now at around 4 million metric tons annually—small compared to the rest of the world, but double what it was in the 1980s. As consumers increasingly seek culinary experiences of both South and East Asia, developers of prepared meals and sides will find ample creative outlets based on the staple grain.

Off the Cob

According to the National Center for Genetic Resources Preservation, in the early 1900s there were 307 varieties of corn. Today, there are only 12 used in mainstream food production. While the decrease in corn types is significant, it is still a diverse and widely used grain. And the diversity is growing again.

While blue corn has been on the edges of popularity for decades in the form of tortillas and chips, purple corn entered the scene about a decade ago and is enjoying a steady rise in use. (In particular, purple corn is enjoying employment as a source of natural coloring.) Red corn, too, is about to claim a corner of the ancient grain trend.

While most red and purple corn products are, as with blue, relegated to tortillas and chips, developers of high-moisture sweet varieties for fresh use will hopefully be able to ramp up production to bring them into other formulations. Sides and salads made with Ruby Queen would not only be eye-catching, but consumers also would be attracted by its higher protein (about 20% higher) and rich antioxidant content.

Colored corn varieties—the full rainbow is available—tend to be higher in starch as well, and so must be picked while “immature” and used quickly. This makes sourcing and consistent quality a challenge for now. Also, the anthocyanins can cause these varieties to change color in production due to heat instability.

This can still be a plus: “The cooking process changes the color of the kernels of fresh sweet red corn,” says Robert Schueller, manager at Melissa’s World Variety Produce Inc. “Boiling actually turns red corn blue, while microwaving turns it purple. Roasting the corn shifts the red color to maroon.”

One of the driving forces behind the use of heirloom grains—and the attraction for

consumers—is a focus on ecologically responsible sustainable farming.

PHOTO COURTESY OF: Danielle Nierenberg and Food Tank (www.foodtank.com)

America's Favorite Snack Gets an Upgrade

In commercial food production, there are four main types of corn: dent, flint, sweet, and popcorn. Popcorn is actually a type of flint corn, but has its own size, shape, starch level, and moisture content. Unlike flint corn, these qualities, precisely cultivated in popcorn, are what make it poppable.

Popcorn was first discovered in the Americas thousands of years ago, and has been delighting consumers for centuries. Interestingly, before modern-day cereals, popcorn was a common breakfast staple. During the Great Depression, popcorn made the shift from the bowl to the snack bag, especially at fairs, parks, and theatres. According to the American Popcorn Board, today, 13 billion quarts of popcorn are consumed annually in the US.

From a manufacturing perspective, popcorn can be a blank canvas. It adapts well to a variety of sweet and savory flavors. Caramel and cheese flavors have long been common, but these, too, are getting makeovers to more artisanal formats using more gourmet cheese flavors and accenting caramel with salt or chocolate. And, of course, popcorn has been on the receiving end of the hot chili pepper craze, getting dusted with everything from jalapeño to habanero and Bhut jolokia (Ghost Chili). And processors are pulling out all the stops to take fuller advantage of this once-simple snack’s versatility.

Flavors recently incorporated into popcorn include everything from truffle parmesan and Canadian maple to chocolate-strawberry. Even more unusual popcorn flavors topped some food trend lists, with combinations such as cardamom-almond butter and saffron-rose.

Originally appeared in the February, 2018 issue of Prepared Foods as Great Grains.