A perennial trend, the culinary traditions of the vast Asian continent are riding a new wave of popularity. This upswing in interest comes from within the mainstream as individual regions jockey for their share of the limelight, and from outside, with smaller countries whose culinary traditions are less familiar to American palates seeking to make their mark.

The former is exemplified by an expansion of Thai cuisine, to include new twists on old favorites and a deeper exploration into regional cooking. Similarly, Vietnamese cooking is experiencing a “back to the roots” movement, taking it beyond the familiar phô into more authentic street cuisine.

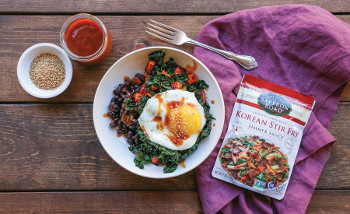

On the less familiar front, Korean cuisine is spiking upward on the popularity of its huge barbecue culture as well as the “new sriracha,” gochujang. Culinologists are applying different forms of fermented pastes and sauces, and relying on umami-rich protein ingredients, ranging from the usual go-to carriers of soy, yeast extracts, and exotic mushrooms, to less familiar umami sources such as chickpeas, sunflower seeds, and grains such as rye.

Korean cuisine, traditionally complex, has taken off as a hot trend, presenting challenges product developers can meet with creative ingredient systems.

PHOTO COURTESY OF: American Halal Co. Inc./Saffron Road Foods (www.saffronroad.com)

Strong Notes

Fermented chili pepper sauces, such as sriracha and sambal oelek, continue to spice up the shelves of today’s retailers, and flavorful heroes such as Korean gochujang (which combines fermented soy and chili peppers) are becoming commonplace in any R&D lab. At the other end of the pH scale, some R&D pros are turning to vinegars (especially sweetened rice vinegar) and other souring agents such as tamarind, citrus juices (such as kaffir lime and yuzu), as either liquids or powders.

Asia includes some 48 countries and holds more than 60% of the world’s population. Most Western consumers use the term “Asian food” to represent a generic, yet tripartate, food group of Chinese/Vietnamese/Thai. However, awareness continues to broaden as each year consumers demand greater and more diverse specificity. This also includes a growing interest in the less familiar cuisines of other countries.

Gabriel Caliendo, chef and vice president of research and development for Lazy Dog Restaurant & Bar Co., declares that Thai, Korean, and Vietnamese, while continuing to grow rapidly, are already well represented. However, he sees “new awareness and possibilities with Laos and Cambodia and their cuisines.”

Northeast Asian countries such as China, Korea, and Japan are still leaders in the region. But Western Asian countries such as Pakistan, Afghanistan, and the areas of China that border them and have large Muslim populations (e.g., Xinjiang Province), bring exotic fusions such as polow, a classic dish somewhere between Chinese fried rice, Indian rice pilaf (biryani), and European paella, but with braised lamb.

Coming to Terms

The terms “traditional,” “authentic,” and “ethnic” are well-worn marketing terms where global flavors are concerned, especially when looking at Asian cuisines. But they also can be controversial due to their generic nature.

“I define ‘traditional’ as a technique and method passed down throughout generations,” says Erika Ellefsen, a research chef for Campbell Soup Co.’s Culinary and Baking Institute. “Think of champagne, for example: it must be made in the traditional “methode champenoise” and the grapes must come from the Champagne region to be considered champagne.”

Packaged versions of popular dishes like Thai coconut chicken soup share many flavors and textures of, and are getting closer to matching, the originals.

PHOTO COURTESY OF: Chef Danhi & Co. (www.chefdanhi.com)

Meanwhile, Paige Norman, executive innovation chef for Applebee’s International Inc., defines traditional as “tried and true flavor combinations that have stood the test of time. They are not a fad; they have true merit.”

Ellefsen further notes that even authentic foods evolve. “A truly ‘authentic’ recipe is like a game of ‘telephone’ that has transpired across several decades,” she says, cautioning, “Things are going to change over time or be miscommunicated, so what can truly be authentic? Getting as close to authenticity as possible is being consistent with traditional techniques, method, and using key ingredients; these all are integral components in making an authentic recipe.”

Ellefsen sees “authentic” as a vague tag. “I struggle with the word ‘authentic’ because no ingredients react the same throughout generations, changes of season, harvesting, use of pesticides or fertilizers, different climates, etc.”

While these parameters might give a lot of leeway in developing a food or beverage that evokes a specific style of cuisine, a research chef or product developer must rely on his or her completely unique flavor experience. R&D professionals must do the research and incorporate that into the development process and venue in order to effectively meet the customers’ expectations.

Playing Center

According to Alexandre Jacques, manager of Quebec East Category for Alimentation Couche-Tard Inc., a leading Canadian convenience store chain, the rich culinary traditions of Central Asia—which includes the Middle East countries of Israel, Lebanon, Syria, and Iran—are still under-represented in the US. He points out that there is great potential, especially now that refugees coming from this region are bringing their heritage and food with them.

Jacques cites the success of—and his own flavorful satisfaction from—chef Yotam Ottolenghi’s eponymous restaurant in London, noting that there is something “truly special as yet untapped.”

Ottolenghi published six cookbooks in rapid succession and all have been relative critical and commercial successes. It could be fair to say they helped reignite interest in the ancient cuisine of this region. (Although the tsunami of a trend that is hummus certainly helped.)

The Middle East is often forgotten as being a part of Asia. The region is well-noted for such fresh foods as vibrant citrus, fruit- and nut-punctuated salads, and overall, its offerings are characterized by brilliant colors and layerings of complex flavors and textures. Yet, at the core, a number of its key foods are reminiscent of those of Southeast Asia, to wit: sandwiches with intensely flavored spreads, grilled meats, and fresh herbs, punctuated with garlic and chili pepper sauce. (Compare to the Vietnamese banh mi.)

Regional Approach

Entrepreneurs from Southeast Asian countries such as Thailand and Vietnam have had tremendous success in establishing local restaurants throughout the US. The culinary creations of these countries also have been segueing into the prepared foods lineup of flavorful players.

While some companies have marketed such items, it still is a challenge to get certain formulations right. Soups, especially, are difficult. Yet, recent years have seen market debuts of authentic phô broth kits that deliver on the layers of flavors inherent in Vietnamese cuisine.

Filipino cuisine combines influences from Chinese and Spanish into a melting pot of a rich culinary heritage.

PHOTO COURTESY OF: Ramar Foods International Inc. (www.ramarfoods.com)

Thailand’s popular galangal-infused coconut chicken soup, tom kha gai, also has facsimiles now available in retail markets. While these dishes share many of the flavors and textures of the original versions, they have yet to capture the flavor and feel of phô or tom kha from a street cart.

On the other hand, perhaps they have paved the way for laksa, a Malaysian and Singaporean version of tom kha gai that is a more complex coconut-enriched lemongrass-chili noodle soup.

As the more established cuisines in the marketplace have strived for greater definition, their facilitators have increased focus on more regional cuisines and styles of eating. For example, Japanese Isakaya, defined as “drinking food” with its roots in the small saké shops that encouraged customers to stay and eat, is making inroads in a US that sometimes has a hard time separating Japanese cuisine from sushi.

The likely impetus has been the great success realized by its “cousin” dim sum, the Chinese tea shop-based foods that have been recently commercialized into a diverse line of retail and foodservice product lines.

Saji Poespowidjojo, product introduction manager for Ajinomoto Foods N.A., spearheaded the development and manufacture of gyoza dumplings typical of the Isakaya style. He notes that he strives to create authentic flavor profiles by mimicking the techniques and methods of those saké shop chefs. One way to achieve the authentic characteristics of gyoza, he says, is through “searing for caramelization and Maillard browning... focusing on evaporation of moisture to concentrate the flavors.”

Taking this to the next level could easily lead to a line of soy-glazed and sesame-sprinkled pork skewers, ready to reheat and serve. Or ginger-mirin and miso-braised pork belly, prepared sous vide. These and similar preparations could conceivably appear soon in the supermarket refrigerator or freezer section.

Southeast Central

In recent years, the US has experienced a significant increase in restaurants featuring the cuisines of the Philippines. As with Indonesian and Malaysian foods, there are some challenges for the prepared foods product developer in recreating those items.

Some traditional Filipino dishes are not inherently visually appealing. They tend toward a narrow range of colors and textures in a single recipe, and in general are not as vibrantly colored nor layered with sensorial variations as many Vietnamese or Thai dishes. Nevertheless, this does not take them out of the race to become the next Southeast Asian star, as they are definitive comfort foods.

Many Asian cuisine styles involve layers of umami, sweet,and sour, brought out by such ingredients as seasoned rice vinegars and citrusy ponzu sauces.

PHOTO COURTESY OF: Mizkan Americas Inc. (www.mizkan.com)

“The Philippines enjoy a strong influence from Chinese and Spanish cultures to create a melting pot with a rich culinary heritage,” says Teresa Oncel, corporate chef for Lee Kum Kee USA Inc. She points out that In Los Angeles, interest in the region’s fare is picking up steam in foodservice. Oncel references restaurants like LA’s Lasa that are experiencing success applying modern refinements to Filipino classics, with a focus on genuine flavors.

Oncel also suggests manufacturers can benefit from adding new twists on products, such as taking the rainbow-colored sweet drink halo-halo and transforming it into an ice cream. Or perhaps adapting the savory garlic-soy-bay leaf chicken adobo to a ready-to-eat rice bowl.

This “re-imagining traditional recipes” approach can be a model for packaged foods, as evidenced by Ramar Foods International Inc. The company has been crafting Filipino frozen desserts, meals, and beverages for nearly half a century.

Ingredient Formats

New market forms of ingredients open up equally new opportunities for culinologists to formulate according to form, function, or flavor. Gochujang, the aforementioned Korean red pepper paste, is typically a thick and sticky paste, making it impractical for some scaling operations of food manufacturers.

Some ingredient makers have solved this challenge by simply making a thinner version; others have turned to newer dehydration technologies such as infrared or vacuum/microwave drying to transform gochujang into dry flakes without adding any carrier, such as maltodextrin.

Authenticity is delivered via such simple methods as using the right version of even basic ingredients— like hom mali rice for a Thai dish.

PHOTO COURTESY OF: Dept. of International Trade Promotion/Thai Trade Center (www.thaitradeusa.com)

In most of these techniques, some heat is applied, not only to increase food safety but also to enhance flavor. This works especially well for preserving and even boosting the spicy fermented umami notes and allowing a sauce that has been traditionally fermented to be used in a dry application.

Commercial packaging of tamarind pulp, palm sugar, coconut milk and cream; dehydrated lemongrass and galangal; powdered soy and other soy-based sauces (see “Soy Story”) and fish sauces; as well as more vibrant flavored lime and other citrus powders, and other versions of ingredients that previously were hard to source or to store has helped research chefs achieve more genuine flavors of Asia in a manufacturing environment.

Soy Story

By Chef Andrew Hunter

Soy sauce, ponzu, mirin, and rice wine—these are the dominant savory notes in many Asian cuisines. They help bring subtle and innovative flavor dimensions in traditional foods as well as unexpected dishes. Some of the tools more recently available to makers of prepared foods and beverages are these same ingredients in dried form.

Dehydrated and granulated forms of soy sauce open up new ways to use the umami power of soy sauce, offering a number of distinct advantages. For example, granulated gluten-free tamari soy sauce is heat-fusible, dispersible, and water-soluble sauce. It provides excellent flavor retention during heat processing and freezing. Dried soy sauce blends well in topical seasoning mixes, and its savory character makes a perfect match in protein dry rubs, spice mixes, and marinades.

Soy sauce and mushrooms are a classic umami combination, and these two work well together in dried formats. In wet marinades, these two powders make beef taste beefier. In teriyaki, powdered soy sauce is a sugar-free way to enhance natural sweet notes without burning or over-caramelization. In other marinades, a combination of liquid soy sauce and powdered soy delivers a deep, more concentrated flavor.

Sweet-savory and even savory ice creams are trending high and can be another unexpected opportunity for using powdered soy sauce. For example, in a roasted pineapple-vanilla-poke ice cream, the roasted notes in the soy enhance the roasted fruit, while the citrus ponzu brightens the sweet flavors.

Sweet-heat combinations work well in ice cream. Developing a chocolate- sriracha-cherry ice cream in which the sriracha isn’t overbearing let it bring a mild end note of heat to the palate, adding a surprising finish to the cooling ice cream. Another combination is ginger-lime-ponzu ice cream that includes the sweet-heat from a praline of wasabi peas. The ginger is prominent in this, and the wasabi doesn’t deliver a burn. The subtle effect of the ponzu ties all the flavors together.

Beverages might not seem like a natural place to use Asian ingredients, but the cocktail bar has become a hub for such experimentation. Ingredients such as bitters, vinegars, and shrubs have brought more savory elements to the beverage category, and Asian flavoring elements are a perfect fit. One example is a Sazerac with the usual rye, absinthe, and bitters, but in this new version, citrus-ponzu-infused cherry adds crowning glory. Drawing inspiration from the classic Loxardo cherry (the original maraschino), cherries are vacuum-sealed with citrus ponzu for a few weeks to infuse flavor. The sour cherry is muddled (pressed) with lemon peel, chilled rye is poured over the fruit, and the top spritzed with absinthe.

Even non-alcoholic drinks can benefit from some Asian infusions. The trend in drinking vinegars calls for experimentation with seasoned rice or sushi vinegars and ponzu to create a limeade drink or an Asian variation on the Arnold Palmer made with jasmine tea and citrus ponzu.

Andrew Hunter is a consulting corporate chef for Kikkoman Sales USA, Inc. and other companies. He earned an AOS in culinary arts from the Culinary Institute of America, a BA in culinary history from New College of Florida, Sarasota and an MA from San Francisco State University.

Originally appeared in the June, 2018 issue of Prepared Foods as Asian Expressions.